Modeling the Value Exchange

The building block for the flow of value

In our last episode, we introduced the notion of value exchanges and collaboration protocols. We used the example of a neighborhood coffee shop to show how we could define value streams as collections of value exchanges in a value network.

This definition of value streams has the advantage of identifying value streams by the value proposition and the characteristics that define how providers and receivers collaborate and assess whether they receive value from a collaboration rather than operational details of how either one fulfills the value proposition.

The value exchange represents the receiver and provider's mutual value assessment process. Each exchange that provides reciprocal benefits enhances the flow of value within the value stream.

The last episode focused mainly on the collaboration protocol and discussed how the two parties assessed value only in high-level terms. Further, the coffee shop was a relatively simple example of a value exchange: providing a repeatable service experience in return for money.

In this post, we will discuss a general structure for the value exchange and look at some more complex examples of value exchanges that we can model using that definition.

Value Exchange Models

This episode is part of a series on Value Networks. Verna Allee developed this modeling technique in the mid-seventies through the early 2000s. It provides a robust formal foundation for reasoning about value in a fundamentally novel way.

The Value Network is a straightforward concept built from three simple primitives: roles, transactions, and deliverables. Roles represent (groups of) people and their roles in value-creating collaborations. Transactions represent interactions between roles, where one delivers something to the other.

Our last episode has a detailed example of a value network and how collaborations are defined in this network.

The key idea behind value networks is that instead of modeling abstract processes, we model how interactions between people create value, and this concept scales from individual interactions to networked ecosystems of people and resources.

A collaboration is a coordinated effort between roles in a value network to achieve shared or complementary goals or desired outcomes. The structure describing the interactions between the roles in a collaboration is called a protocol.

In our last episode, we showed a few examples of collaboration protocols in a value network for the coffee shop, and how they gave rise to distinct value streams in the network.

With this as a preamble, let's formalize the definition of “value exchange.”

In a value exchange model, the deliverables are the tangible or intangible outputs exchanged, while the value model captures the value outcomes expected and derived by each party.

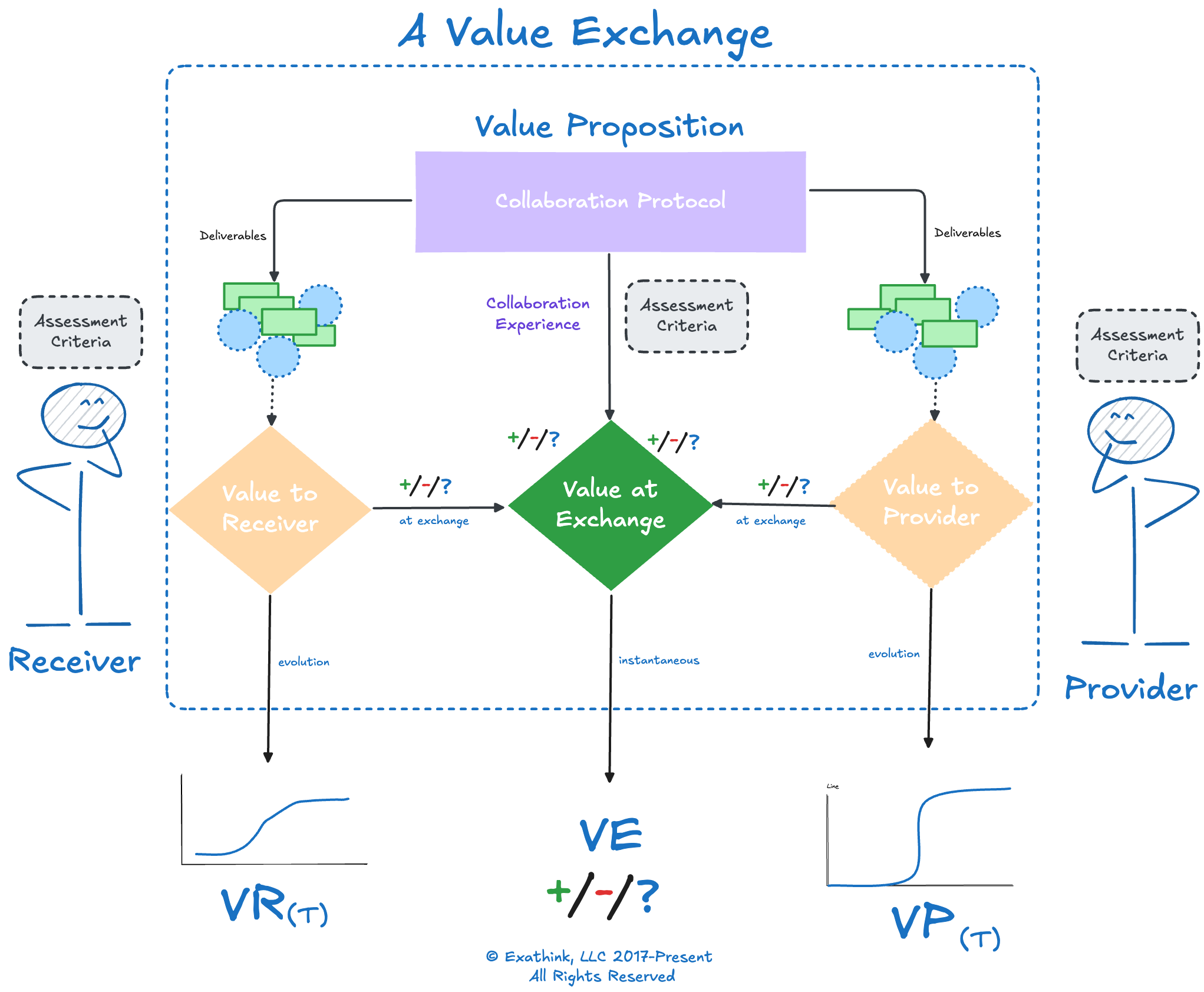

A value exchange model describes the value semantics of a collaboration. It provides a framework for assigning a multi-dimensional score to an instance of collaboration based on an independent assessment of the deliverables exchanged by two roles: the provider and receiver.

In a value exchange, the provider presents a value proposition to the receiver. The parties then evaluate the deliverables exchanged using a value model as a rubric. Both parties assess the collaboration using desired and undesired attributes from the value proposition, describing the value generated from the exchange.

The assessments may be subjective or objective and may or may not be directly observable or measurable1. The value model is an abstract representation of a decision process that measures value in a value exchange.

The dimensions, structure, units of measurement, and assessment criteria will depend on the context. However, we can identify the model's components.

A collaboration with a set of protocols and two identified roles, a provider and a receiver.

The value proposition2 states the desirable and undesirable outcomes regarding the attributes of the tangible and intangible deliverables exchanged in the collaboration.

Value-at-Exchange (VE): The shared value assessment between the provider and receiver catalyzes the exchange. It may be expressed as a monetary payment, barter, or as other intangibles, but it describes the exchange's underlying drivers and value expectations. The critical thing to note about value-at-exchange compared to the other two components is that it records the value perceived by both parties in engaging in the exchange at the time of the exchange.

Value-to-Receiver (VR): This is the totality of benefit or utility to the receiver from the exchange. It could be functional (e.g., a product's features meeting a need), emotional (e.g., satisfaction or trust), symbolic (e.g., status or affiliation), or some other combination of all the above. These are evaluated using the assessment criteria of the deliverables from the provider as assessed by the receiver. Value-at-exchanges includes components of the value-to-receiver.

Value-to-Provider (VP): This represents the totality of benefits the provider receives from the exchange. It could include revenue, profit, reputation, customer retention, or any other measurable gain that makes the exchange worthwhile for the provider. The value may also include long-term strategic outcomes like increased market share or customer lifetime value for the provider. These are evaluated using the assessment criteria of the deliverables from the receiver as assessed by the provider. Value-at-exchanges includes components of the value-to-receiver.

VE may also include assessments of the attributes of the collaboration experience that are valuable to either role, such as speed and efficiency in completing the collaboration. While value-at-exchange is typically known at the time of exchange, some components of value-to-receiver and value-to-provider may not be fully known until after the exchange.

Sometimes, the value received is realized over more extended time frames. In many other cases, the value obtained may not be attributable to a single value exchange but the cumulative result of many related and independent value exchanges between the provider, the receiver, and other parties.

A party may even enter into an exchange when they understand that they may not receive value directly from it, i.e., no value-at-exchange, provided they believe they will eventually receive value as a cumulative result of future value exchanges.

In the Zeptos example, there is no real difference between value-at-exchange and the other two components. Here, both parties can evaluate an entire collaboration at or close to the exchange time. All value exchanges happen instantaneously.

This is not generally true, so in those cases, we record the value assessment at the time of exchange using value-at-exchange and separately specify the other two components.

This is necessary to model complex scenarios, such as deferred value creation, value created through network effects, and interactions with other value exchanges.

As we will elaborate in later posts, the outputs VR, VE, and VP from the value exchange model are best viewed as inputs into a larger causal model for the network's value flow.

But first, let’s look at another example to illustrate a more complex value exchange.

An automobile

Durable goods or high-ticket items like automobiles surface more interesting questions about modeling value exchanges.

While the value-at-exchange is often shaped by straightforward factors like price, utility, and brand reputation, the value-to-receiver and value-to-provider incorporate longer-term considerations such as reliability, maintenance costs, and residual value. The protocol between the buyer and dealer to successfully buy an automobile is often complex, and this buying experience can significantly impact the buyer's perception of value.

Further, whether a transaction is a purchase or a lease significantly impacts the value exchange3. In a purchase, the buyer takes ownership of the vehicle and, in addition to its base utility, focuses on long-term considerations like reliability and residual value. In a lease, short-term affordability, flexibility, and terms take precedence.

For the provider, leasing offers recurring revenue and retention opportunities, whereas purchases deliver higher upfront profit. Since the provider retains ownership of the vehicle, leasing carries risks, such as uncertainty about depreciation and potential losses if the vehicle’s residual value falls short of projections.

Notably, the cumulative value to the customer or provider often remains unclear until a subsequent vehicle transaction, such as resale, trade-in, or lease return, reveals how well the car met value expectations over time. These are also subject to external factors like the state of the economy, interest rates, etc. Nevertheless, they may impact the sustainability of the value stream between the buyer and the dealer.

Therefore, the flow of value between dealer and buyer is multifaceted and evolves as immediate factors like price and contract terms interact with longer-term considerations such as reliability, residual value, and the outcomes of subsequent exchanges. Transactions such as selling, trading in, or returning a leased vehicle or service costs over time clarify the true value both parties realize.

For buyers, they highlight how well the vehicle met expectations, while for dealers, they involve managing residual value risks, reselling opportunities, and fostering customer loyalty for future business.

It is impossible to truly speak of this value network's “flow of value” without modeling these particulars in an explicit value model.

More Examples

While the examples above may have given a flavor of what is involved in creating a meaningful model for the flow of value in a value network, they are just the tip of the iceberg regarding the subtleties involved.

As an exercise, the interested reader can consider how they might model other value networks and value exchanges within them, such as

Extending the Give Review transaction in the Zeptos example to include reviews given on a third-party site.

Two-sided marketplaces, such as food delivery or rideshare platforms, involve an intermediary in the value exchanges between providers and receivers.

Financial transactions, including buying, selling, or shorting stocks in the stock market.

A social media platform as a value network.

The relationships between a company and its employees as a value network.

Modeling the flow of value in these types of networks can provide fascinating insights into reasoning about “value.” We will continue to post occasional examples of such exchanges on this blog.

From Goods to Services

Both value exchange examples discussed so far involve tangible goods exchanged for money, a model that dominated economic discourse throughout the 20th century. In the 21st century, however, intangibles like software IP, information services, and technology-powered business networks have become the primary drivers of value creation.

Value exchanges and value models in these networks are far more nuanced, involving intangible exchanges, value creation through network effects, and delayed or deferred value realization for network participants. Most businesses today are service-oriented, with tangible goods, if any, subordinated to the services they provide to customers.

Services leverage the knowledge and skills of participants directly within the network, often augmenting and enhancing tangible goods that package other forms of expertise. Software products exemplify this shift, representing some of the most complex and dynamic forms of value creation that blend goods-dominant and service-dominant4 dynamics. These changes fundamentally transform how value is created and exchanged beyond the straightforward exchanges of tangible goods for money.

In a goods-dominant economy, value creation could be compartmentalized: product development, production, distribution, and marketing were distinct “activities,” with each “adding value” sequentially to a tangible deliverable until it reached the customer. The “added value” is reflected in the value-in-exchange, typically in the price.

In our next post, we’ll argue that much of the current thinking around Lean value streams is deeply rooted in this goods-dominant model. While effective for its time, this framework fails to address the complexities of value creation in a service-dominant economy. We propose that value networks and value exchanges are better suited for this purpose and specialize naturally for goods-dominant value streams.

Lean value stream concepts are still valuable for analyzing and improving the “flow of deliverables” within a value network, where much of the true focus of value stream management remains.

Still, the broader “flow of value” often remains obscured at that level of detail in service-dominant value networks, and it is worthwhile to examine the definition of value streams more critically in this light.

The key flaw in current value stream management practices is that they conflate the “flow of value” with the “flow of deliverables.” While this conflation works somewhat in a goods-dominant domain, it certainly does not work in general service-dominant domains.

So, in these domains, we need to start by clearly understanding the “flow of value” in the value network before focusing on improving the “flow of deliverables” within it. As we have seen in the Zeptos and automotive retail examples, this separation of concerns is appropriate even in nominally goods-dominant domains like automotive retail once you factor in all the services involved in value creation.

In the next episode, we will describe the differences between services-dominant and goods-dominant value streams and discuss what this means when identifying, modeling, and managing them.

Acknowledgments: Mark Smalley introduced me to the concepts of service-dominant logic, for which I will be forever grateful. Tom Gilb was kind enough to review an early draft of this post and gave me insightful feedback that I am still digesting. Marc Charron reviewed this post while it was still part of the previous post and encouraged me to break it up into two posts :)

The question marks in the diagram indicate that some assessment criteria may not be directly observable or measurable at all times. The assessment criteria are, in general, signals, and the measurement strategy for the signals is not a core part of the value exchange model.

The value proposition is usually defined as the provider expressing the receiver's needs. Of course, refining the value proposition to match the actual needs is the key problem the provider needs to solve. This means identifying the deliverable attributes that the receiver cares about. This is at the heart of the value modeling exercise and is context-specific.

In general, whether the exchange involves transferring ownership, possession, or availability of a deliverable significantly impacts the flow of value in the network. Pavel Hruby’s seminal contributions have significantly influenced my thoughts on value exchanges.

The concepts of Service-Dominant Logic were developed by Stephen Vargo and Robert Lusch and are summarized well in this clear and accessible paper. Many thanks to Mark Smalley for introducing me to these concepts.